[ad_1]

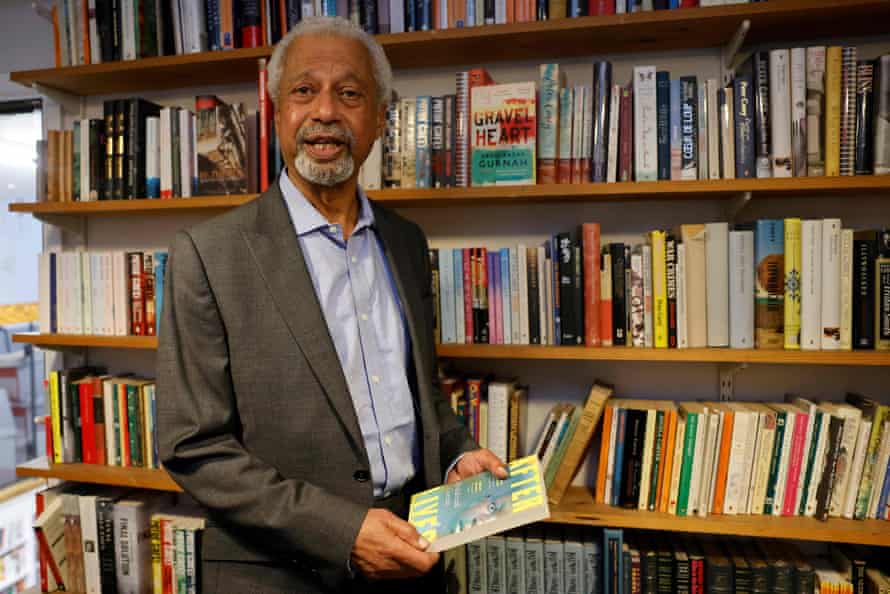

Abdulrazak Gurnah appears preternaturally calm for somebody who has all of the sudden discovered themselves within the full glare of the world’s media. “Simply superb,” he solutions once I ask how he’s feeling. “A bit bit rushed, with so many individuals to fulfill and communicate to. However in any other case, what are you able to say? I really feel nice.” I meet the newly minted Nobel literature laureate surrounded by books in his agent’s workplace in London, the day after the announcement. He appears to be like youthful than his 73 years, boasts a full head of silver hair, and speaks evenly and intentionally, his expression barely altering. The adrenaline rush, if he skilled one, is hardly in proof. He even slept fairly properly.

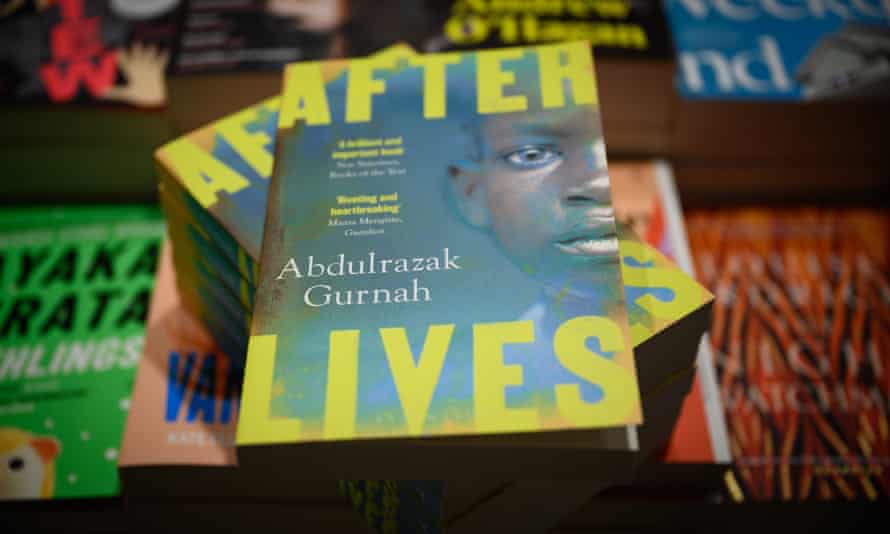

All the identical, just a little over 24 hours in the past, he was merely the critically acclaimed creator of 10 novels, at residence in his kitchen in Canterbury, the place he lives after having retired as a professor of English on the College of Kent. Now, a brand new degree of celeb beckons – albeit of a rarefied variety. The Swedish Academy’s quotation referred just a little ponderously to “his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the consequences of colonialism and the destiny of the refugee within the gulf between cultures and continents”. Others have a good time the lyricism of his writing, its understated, wistful brilliance.

At first he didn’t imagine it. “I assumed it was a type of chilly calls. So I used to be simply ready to see – is that this an actual factor? And this very well mannered, mild voice stated, ‘Am I speaking to Mr Gurnah? You’ve gotten simply gained the Nobel prize for literature.’ And I stated, ‘Get off! What are you speaking about?’” He wasn’t totally satisfied till he learn the assertion on the Academy’s web site. “I attempted to ring Denise, my spouse. She was out with the grandson on the zoo. So I received her on the telephone, however on the identical time the opposite telephone’s going and there’s someone from the BBC wanting stuff.”

The win is a landmark. Gurnah is just the fourth black individual to win the prize in its 120-year historical past. “He is among the biggest dwelling African writers, and nobody has ever taken any discover of him and it’s simply killed me,” Alexandra Pringle, his longtime editor, advised the Guardian final week. I ask if this comparatively low profile (he was shortlisted for the Booker prize in 1994) had ever received him down. “I feel Alexandra was most likely which means that she thought I deserved higher. As a result of I didn’t assume I used to be ignored. I turned comparatively content material with the readers that I had, however after all I can do with extra.”

Gurnah grew up on Zanzibar, off the coast of Tanzania, within the Fifties and 60s. Since 1890, the island nation had been a British protectorate, a standing that Lord Salisbury described as “cheaper, easier, much less wounding to … vanity” than direct rule. For hundreds of years earlier than that, it had been a hub for commerce, notably with the Arab world, and a fantastic melting pot. Gurnah’s personal heritage displays this historical past, and he was raised Muslim (not like Zanzibar’s different well-known son Freddie Mercury, whose household have been Zoroastrians, initially from Gujarat).

In 1963, Zanzibar turned unbiased, however its ruler, Sultan Jamshid, was overthrown the next 12 months. In the course of the revolution, wrote Gurnah in 2001, “1000’s have been slaughtered, entire communities have been expelled and lots of tons of imprisoned. Within the shambles and persecutions that adopted, a vindictive terror dominated our lives.” Within the midst of this turmoil, he and his brother escaped to Britain.

A number of of his novels cope with leaving, dislocation and exile. In Admiring Silence, the narrator, although he builds a life and household for himself in England, finds himself neither English nor any longer Zanzibari. Does Gurnah’s personal rupture along with his personal previous nonetheless hang-out him? “‘Hang-out’ is to melodramatise it,” he says. Even so, the topic of displacement fascinates him – and it isn’t getting any much less related. “This can be a very massive story of our occasions, of individuals having to reconstruct and remake their lives away from their locations of origin. And there are a lot of totally different dimensions to it. What do they bear in mind? And the way do they address what they bear in mind? How do they address what they discover? Or, certainly, how are they acquired?”

Gurnah’s personal reception, in late 60s Britain, was incessantly hostile. “After I was right here as a really younger individual, individuals wouldn’t have had any drawback about saying to your face sure phrases that we now think about to be offensive. It was far more pervasive, that kind of angle. You couldn’t even get on a bus with out one way or the other encountering one thing that made you recoil.” Overt, confident racism has for essentially the most half diminished, he says, however one factor that has barely shifted is our response to migration. Progress on that entrance is essentially illusory.

“Issues seem to have reworked [but] then we’ve new guidelines about detention of refugees and asylum-seekers which can be so imply they appear to me to be nearly felony. And these are argued for and guarded by the federal government. This doesn’t appear to me to be an enormous advance to the way in which earlier individuals have been handled.” The institutional reflex to push away those that come right here seems to run deep.

I’m about to say residence secretary Priti Patel, at present answerable for one of many establishments doing the pushing, however he beats me to it. “The curious factor, after all, is the individual presiding over that is herself someone who would have come right here, or her mother and father would have come right here, to confront these attitudes themselves.” What would he say to her if she have been right here now? “I might say, ‘Possibly just a little extra compassion may not be a foul factor.’ However I don’t wish to get right into a dialogue with Priti Patel, actually.”

What was his response to the Windrush scandal, which noticed 1000’s threatened with deportation regardless of having come to Britain from the Caribbean many years in the past? “Properly, it actually wasn’t a shock.” That doesn’t make it any much less heartbreaking, after all. “The main points are at all times transferring, as a result of they’re about actual individuals. However the phenomenon itself – it may have been predicted.” And will occur once more sooner or later, I recommend. “It’s most likely occurring as we communicate,” he replies, gloomily.

Gurnah lived for 17 years in Britain earlier than setting foot in Zanzibar once more. Within the meantime he had blossomed right into a author. “The writing was sort of occasional. It wasn’t one thing the place I assumed, ‘I wish to be a author’ or something like that.” Nonetheless, the circumstances have been one way or the other proper. “Writing [came] out of the state of affairs that I used to be in, which was poverty, homesickness, being unskilled, uneducated. So out of that distress you start to put in writing issues down. It wasn’t like: I’m writing a novel. However this saved rising, these items. Then it began to turn into ‘writing’ as a result of it’s important to assume and assemble and form and so forth.” What was it like, that first journey again? “It was terrifying: 17 years is a very long time and, after all, as with lots of people who relocate or who transfer away from their properties, there are all types of problems with guilt. Presumably disgrace. Not figuring out for positive that you just’ve accomplished the best factor. But additionally not figuring out what’s going to they consider you, you understand, that you just’ve modified, you’re not ‘one in every of us’. However the truth is, none of that occurred. You step off the airplane and everyone’s blissful to see you.”

Does he nonetheless really feel caught between two cultures? “I don’t assume so. I imply, there are moments like when, after the [attacks on] the World Commerce Middle, for instance, there was such a violent response to Islam and to Muslims … I suppose in case you determine as being a part of this maligned group, then you definately would possibly really feel a division, you would possibly really feel – is there one thing behind an encounter you’ve with someone?”

Each inhabitant of Zanzibar is aware of about Britain. But it surely’s most likely honest to say that, on listening to the place the brand new Nobel laureate grew up, lots of his fellow Britons will ask: “The place’s that?” On one degree, it’s an comprehensible asymmetry, given how small Zanzibar is (about 1.5 million individuals stay there). However does Gurnah assume the British know sufficient basically in regards to the historical past of their affect around the globe? “No,” he says, baldly. “They find out about some locations that they wish to find out about. India, for instance. There’s this kind of love affair occurring, no less than with the India of the empire. I don’t assume they’re so eager about different much less glamorous histories. I feel if there’s just a little little bit of nastiness concerned, they don’t actually wish to find out about that very a lot.”

Then again, he says, this isn’t essentially their fault. “It’s as a result of they don’t get advised about this stuff. So you’ve on the one hand scholarship, which deeply investigates and understands all of those dimensions of affect, the implications, the atrocities. Then again, you’ve a well-liked discourse that may be very selective about what it’ll bear in mind.” Can different kinds of storytelling fill the hole? “It appears to me that fiction is the bridge between this stuff, the bridge between this immense scholarship and that sort of common notion. So you’ll be able to examine these issues as fiction. And I hope that the response then is to say, ‘I didn’t know that’ and probably for the reader, ‘I need to go and browse one thing about that.’”

That should be one in every of his hopes for his personal work? “Properly,” he solutions, in a tone that implies he doesn’t relish being categorised as an “eat your greens” author, “it’s not the one necessary factor about writing fiction. You additionally need the expertise to be pleasurable and fulfilling. You need it to be as intelligent and as attention-grabbing and as stunning as doable. So a part of it could be to interact, however to interact as a way to say, ‘That is maybe attention-grabbing to find out about, however it’s additionally about understanding ourselves, understanding human beings and the way they address conditions.’” In different phrases, the setting could also be specific; the expertise common.

Gurnah says he doesn’t know what he’s going to do with the £840,000 prize cash. “Some individuals have requested. I haven’t the faintest thought. I’ll consider one thing.” We agree that it’s a pleasant drawback to have. After which there’s the query of what it’s prefer to be essentially the most well-known Zanzibari since Freddie Mercury. “Yeah, properly, Freddie Mercury is known right here – he’s not likely well-known in Zanzibar, aside from individuals who need vacationers to return into their venues. There’s an exquisite bar, which a relative of mine owns, known as the Mercury. However I feel if I have been to ask someone on the street, ‘Who’s Freddie Mercury?’ they most likely gained’t know. Thoughts you,” he laughs, “they most likely wouldn’t know who I’m both.”

That will as soon as have been the case, however as the primary black African to win the prize in additional than three many years, Zanzibar – and the world – could now be able to pay a bit extra consideration to him.

[ad_2]

Source link