[ad_1]

On 2 November, the Chinese language tennis star Peng Shuai posted an extended message on the social media web site Weibo, accusing China’s former vice-premier, Zhang Gaoli, of sexual assault. As quickly because the publish went reside, it turned the highest-profile #MeToo case in China, and one of many ruling Chinese language Communist occasion’s largest public relations crises in current historical past. Inside about 20 minutes, the publish had been eliminated. All mentions of the publish have been then scrubbed from the Chinese language web. No references to the story appeared within the Chinese language media. Within the days that adopted, Peng made no additional statements and didn’t seem in public. Exterior China, nevertheless, as different tennis stars publicly expressed issues for her security, Peng’s obvious disappearance turned one of many greatest information tales on this planet.

It wasn’t lengthy earlier than Hu Xijin stepped into the story. Hu is the editor of the International Instances, a chest-thumpingly nationalistic tabloid typically described as “China’s Fox Information”. Lately, he has develop into essentially the most influential Chinese language propagandist within the west – a continuing presence on Twitter and within the worldwide media, at all times readily available to defend the Communist occasion line, regardless of the subject. On 19 November, he tweeted to his 450,000 followers that he had confirmed by means of his personal sources – he didn’t say who they have been – that Peng was alive and properly. Over the subsequent two days, he posted videos of Peng at a restaurant and signing autographs in Beijing.

Get the Guardian’s award-winning lengthy reads despatched direct to you each Saturday morning

To many observers, this seemingly stage-managed footage, disseminated by organs of the Chinese language state, was not reassuring. On 21 November, the Worldwide Olympic Committee spoke with Peng on a video name and declared that she was “doing wonderful”. When this intervention nonetheless didn’t persuade many who Peng was protected, Hu took the chance to hammer residence one of many central themes of his three-decade profession in journalism: on the subject of China, the western media sees solely what it needs to see. “They solely imagine the story about China that they think about,” he tweeted. “I’m stunned that they didn’t say the girl who confirmed up these two days is a faux Peng Shuai, a double.” Those that continued to query Peng’s security, Hu wrote, have been attempting to “demonize China’s system”.

Hu’s eagerness to reframe a narrative about sexual assault and censorship as a narrative about clashing political ideologies and anti-China prejudice is a part of a major change in the way in which China presents itself to the world. From the late Seventies onwards, as China was opening up however had but to imagine a significant position in worldwide affairs, it struggled to deal with criticism from overseas. The official response was normally some type of wounded denial, or a stilted demand that different international locations keep out of its enterprise. However over the previous decade, as China’s world energy has grown, President Xi Jinping has pushed the nation right into a extra assured, aggressive posture, and Hu, greater than some other Chinese language journalist, has develop into the voice of this pugnacious nationalism. On China’s hottest social media platform, WeChat, the International Instances is reportedly essentially the most learn outlet.

“My English is sort of all self-taught,” Hu as soon as mentioned in a video on Weibo, “and in English, I’m most skilful at choosing a battle.” He has overrated the prospects of army confrontation between the US and China over Taiwan. He has warned that if Britain infringes Chinese language sovereignty within the South China Sea then will probably be handled like “a bitch” who’s “asking for a beating”. He has in contrast India to a “bandit” that has “barbarically robbed” Chinese language corporations. He has referred to Australia as nothing greater than “gum caught to the underside of China’s shoe”. He lately concluded an article with the query: “Within the face of such an irrational Australia, shouldn’t China be ready with an iron fist and to punch it laborious when wanted, educating it an intensive lesson?”

When he picks a battle with international officers on Twitter, Hu likes to take screenshots of the tweets and publish them on Weibo, simply to point out his 24 million followers – most of whom are blocked from Twitter by the nice firewall – that he’s on the market, defending China’s honour. “A very powerful factor about Hu is that he has constructed a complete model of authoritarian, nationalistic rhetoric,” Xiao Qiang, an skilled in Chinese language media at Berkeley’s Faculty of Info, advised me. “His readers go round repeating the identical issues and spreading the identical sentiments.” Hu’s combative method has been taken up by a variety of Chinese language diplomats and spokespeople – usually referred to as “Wolf Warriors”, in reference to a jingoistic Chinese language blockbuster film – who promote a “China first” philosophy and use social media to trash anybody they see as opposing Chinese language pursuits. However the place the Wolf Warrior diplomats are a current phenomenon, individuals like Hu “have been propagating this concept for 10 years,” says Xiang Lanxin, a professor of worldwide politics at Geneva’s Graduate Institute.

Hu’s limitless stream of quotable insults and invective stands out amid a sea of bland official statements, calls to “occupy new platforms for occasion discourse”, and so forth. As soon as you recognize his title, you see him quoted all over the place – the BBC, NPR, the Monetary Instances, the Washington Submit, the Instances, Reuters. Previously two years, the New York Instances has talked about him 46 occasions. “He’s prepared to be quoted within the Xi Jinping period, when large numbers of others – particularly liberal commentators – have grown too nervous to go on-the-record with international journalists,” says Evan Osnos, who has written about China for the New Yorker since 2008. Hu has even develop into the topic of headlines in his personal proper. “Editor of Chinese language state newspaper which routinely mocks Australia loved LUNCH at our embassy”, reported Day by day Mail Australia final yr.

One cause for Hu’s ubiquity is that he has unparalleled licence to talk bluntly about politics. Hu’s home critics have described him as “the one individual with freedom of speech” in mainland China, although that freedom is partly a mirrored image of his adherence to the CCP line. Hu’s insistence on thrusting himself into each passing controversy has earned him the nickname diaopan, or “Frisbee catcher” – like a loyal pet, he tries to convey each argument residence for the federal government he serves.

Over time, Hu has inspired a sort of mystique round his reference to occasion management. “To be trustworthy, I actually don’t know for positive to what diploma I mirror the authority’s voice,” Hu advised me after we spoke on the cellphone late final yr. He likes to say that the International Instances’ success is a product of the market. However after I requested him if the paper is financially impartial from the federal government, he ultimately advised me, after some forwards and backwards, that the English version receives authorities funding for offering abroad propaganda.

The place Hu as soon as spoke for a hardline fringe of the Communist occasion, his newspaper’s aggressive China-first ideology is now ascendant. As one American creator who stopped writing for the International Instances in 2011 put it: “With all these Wolf Warrior diplomats, it’s like the federal government has been International Instances-ified.”

In 2016, President Xi visited the Beijing headquarters of the Individuals’s Day by day, the most important newspaper group in China, which is run by the Communist occasion and publishes Hu’s International Instances. On his tour of the workplaces, as he handed by means of the exhibition corridor, Xi pointed approvingly to a show copy of the International Instances and declared himself a reader. Hu, it appeared, was efficiently pursuing the propaganda technique that Xi had laid out early in his presidency.

Hu’s rise is difficult to understand with out understanding the broader story of free speech in twenty first century China. Within the 00s, tons of of hundreds of thousands of Chinese language residents got here on-line and their voices turned extra audible. Beginning in 2008, the Individuals’s Day by day arrange a devoted crew to watch public opinion on-line. Its first few annual studies introduced new digital platforms in a constructive gentle, as a technique to convey the federal government and its individuals nearer. Weibo and different on-line communities have been “a very good software for residents to take part in and focus on politics,” the 2010 report said. Throughout this era, journalists in China have been afforded slightly extra freedom to do reporting that touched upon politically delicate points, although sure matters – such because the 1989 Tiananmen Sq. bloodbath, and the lives and conduct of prime management – remained off-limits.

Beginning within the early 2010s, and significantly from 2012, with the rise of Xi, this extra liberal method to public discourse was step by step reversed. “When Xi Jinping turned president [in 2013], he was not within the voices on the web,” Xiao, the UC Berkeley professor, advised me. “As a substitute, he perceived such voices as a menace to his energy, and recognised that it was time for a whole crackdown.” Posts on social media, reminiscent of Weibo, turned more and more monitored and censored. It turned extra widespread for net customers to obtain an “invitation to tea”, a euphemism for a cellphone name instructing you to go to your native police station to reply questions on your on-line actions. From 2013, a rising variety of residents have been suspended or banned from on-line platforms, detained or sentenced to jail. Drawing on media studies and court docket paperwork, an online database recorded greater than 2,000 instances by which individuals had been punished or prosecuted for his or her on-line speech since 2013. The whole quantity is sort of definitely a lot increased.

In 2013, on the identical time the occasion was tightening its grip on public discourse, Xi referred to as a convention with propaganda officers from throughout the nation, urging them to “inform the China story properly”. That meant overlaying China in a method that was constructive, participating and harnessed new digital platforms. It meant proudly celebrating China’s achievements, moderately than specializing in its imperfections.

Hu tailored fluidly to China’s new media surroundings, which was directly very on-line, obedient to the occasion line and international-facing. In his articles, social media interventions and interviews, he performed the position of each dutiful defence legal professional – there to ship the occasion’s aspect of the story, regardless of how implausible it might sound – and aggrieved relative of the accused, yelling out to the court docket that the prosecution and the decide have been prejudiced or corrupt or silly, or all the above. It was a mode that suited the tenor of Chinese language social media, in addition to the brand new self-image of the Communist occasion. Different occasion media retailers began to imitate Hu’s model, writing in a extra colloquial method. Even Individuals’s Day by day, famously stolid and unvoiced all through most of its historical past, encourages its commentators to be extra “enjoyable” and to develop private manufacturers.

In 2019, Xi visited the Individuals Day by day’s workplace once more. He requested the nation’s media employees to embrace new expertise to “maximise and optimise propaganda impression” and “to advertise the voice of the occasion instantly into numerous apps and occupy new platforms for occasion discourse”. As Xi cruised by means of the workplace, the Individuals’s Day by day editorial crew lined up and applauded. Amongst them was Hu in a darkish gray jacket, smiling ear to ear.

No occasion appears to distil Hu’s outstanding place in Chinese language journalism just like the Tiananmen Sq. bloodbath. Journalists are at all times proud to inform their readers that they have been there when one thing vital occurred. Hu does the identical on the subject of Tiananmen, besides that he inserts himself into this historical past with a purpose to discredit it. References to the Tiananmen bloodbath are prohibited in China. Maybe the one exception to this rule is the International Instances. When Hu writes in regards to the topic, he paints it as a harmful folly. “If the incident 32 years in the past has any constructive impact,” Hu wrote this June, “it has inoculated the Chinese language individuals with a political vaccine, serving to us purchase immunity from being severely misled.”

Hu was 29 when the pro-democracy protests started. He had been born right into a poor, Christian, however in any other case conventional household. His father was an accountant at a manufacturing unit that manufactured rockets, and his mom, who was illiterate, made embroidery with a stitching machine to usher in some additional revenue. At 18, Hu joined the Individuals’s Liberation Military and enrolled in its foreign-language school in Nanjing, the place he majored in Russian. In 1986, nonetheless a army officer, he began a masters programme in Russian at Beijing International Research College. Within the spring of 1989, when protests erupted throughout the nation, Hu was months away from commencement. “I went to Tiananmen Sq. each day, chanting slogans like everyone else,” Hu advised a Chinese language reporter in 2011. (Xiao, the UC Berkeley professor, who was a pupil at Notre Dame in 1989 and flew again to Beijing upon seeing the information on TV, laughed at the concept that Hu may have been there as a protester. He famous that the army school Hu attended is typically often called “China’s cradle of 007s”. “If he actually participated within the protest, god is aware of what his position was,” Xiao mentioned.)

Shortly after the violent suppression of the Tiananmen protests, Hu joined the Individuals’s Day by day newspaper, the place he spent two years as a researcher and one other two years as an editor on the night time shift. On the time, China was greater than a decade into Deng Xiaoping’s push to develop a market financial system. Hu was a part of a gaggle of journalists on the Individuals’s Day by day who sought to create new income streams by launching a weekly newspaper referred to as International Information Digest.

On 3 January 1993, 20,000 copies of the primary situation, which included a narrative on Diana, Princess of Wales’s break up from Prince Charles, appeared on newsstands. The entrance web page featured a grandiose message from the editors, which proclaimed that after 500 years of falling behind the west, and 14 years of financial reform, China was “saying goodbye to poverty and backwardness, like an enormous dragon about to take off, standing tall within the east of the world, its head held excessive”. Regardless of this lofty rhetoric, Hu claims there wasn’t a transparent imaginative and prescient at first. “We revealed no matter extraordinary individuals preferred to learn,” he advised me.

The publication was crammed with unique tales about spies, royal romances, historic assassinations and kids raised alongside wild animals. Most mainstream publications have been so propaganda-heavy, so crammed with occasion lingo and information of prime leaders’ limitless conferences, that the arrival of the plain-talking, eye-catching International Instances should have felt like an episode of Intercourse and the Metropolis beamed into the center of an extended sermon. Articles from the 90s included The Darkish World of the Russian Mafia, From Feminine Slave to Style Mannequin, and The Surprising Insanity of Monks: Korean Buddhists’ Rivalry Doused Monastery with Blood.

A number of months into his stint at International Information Digest, Hu’s profession was remodeled when he was dispatched overseas to cowl the Bosnian struggle for the Individuals’s Day by day. In his memoir in regards to the expertise, revealed in 1997, he recalled considering that the very fact of a Chinese language journalist reporting on a international struggle “was possible extra newsworthy than no matter articles he has to file”. To Hu, the battle in Bosnia turned the backdrop for a non-public battlefield in his thoughts, as he started measuring himself towards the western journalists round him, whom he each admired and resented. “To be a soldier in a contemporary information struggle, I couldn’t defeat the western reporters, however I congratulate myself for with the ability to even be part of them for a battle,” Hu wrote in his memoir. (Nearly 1 / 4 of a century later, his Twitter avatar is a photograph of him in Sarajevo, sitting on the curb taking notes.)

The guide is sprinkled with a combination of satisfaction and vulnerability, as Hu struggles along with his personal inferiority complicated: “Why can’t I be the one who creates a sensation? Why can’t a Chinese language reporter be within the limelight?” he writes at one level. He admits that he spent his time obsessing over methods to “look extra like an actual reporter”, moderately than specializing in reporting. “I couldn’t stand being regarded down upon, not solely on a private stage, but in addition on the account of being Chinese language – a undeniable fact that brings with it a sort of insufferable stress for me.” He carried this chip on his shoulder all over the place he went. On one event, he turned as much as a information briefing that was in Albanian. He didn’t perceive a phrase, however that didn’t cease him from asking a query in English – to not search a solution, simply to say his presence.

Hu returned to Beijing in 1996 and shortly turned International Information Digest’s deputy editor. “I used to be a struggle and worldwide affairs reporter, and my private curiosity was fused into our protection,” he advised me. In 1997, the paper modified its title to the International Instances, and within the subsequent two years, circulation tripled. “China was turning into built-in with the world,” Hu mentioned. “Previously, worldwide information have been merely items of data or data from distant corners of the world. Regularly, worldwide information turned increasingly associated to China, and the Chinese language viewers developed a eager curiosity in what’s taking place exterior the nation.”

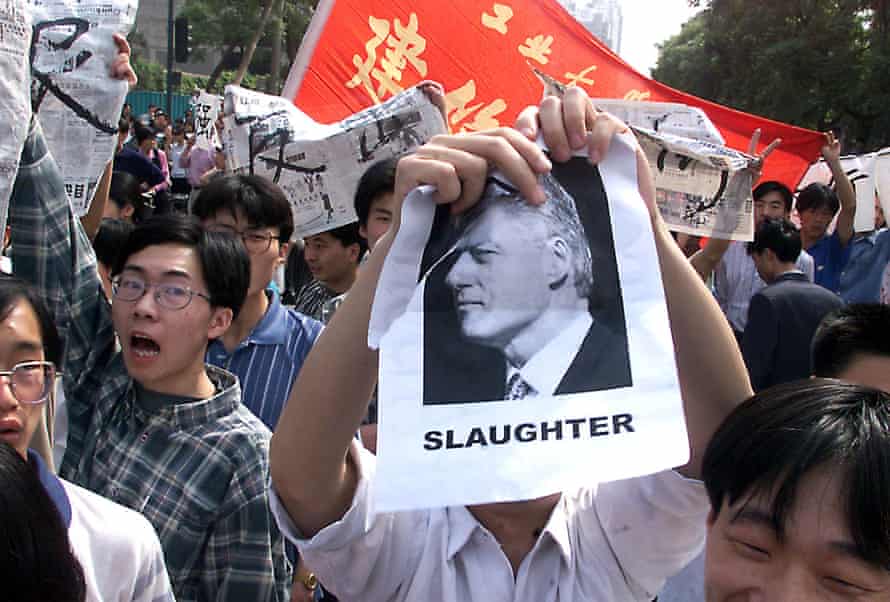

One worldwide incident from this era symbolised that new actuality. On 7 Might 1999, a Nato bomb hit the Chinese language embassy in Belgrade, killing three Chinese language journalists. Officers from the US claimed that it was an accident and that the true goal had been a Yugoslavian defence company a number of hundred metres down the street. However many individuals in China believed it was a deliberate assault, and anti-American protests erupted throughout the nation. Two days after the bombing, the International Instances revealed a particular situation, that includes a report by a International Instances journalist who had been talking with the ambassador within the constructing simply minutes earlier than the explosion. In line with Han Rongbin, a professor of worldwide affairs on the College of Georgia, occasions such because the embassy bombing strengthened a collective sense of aggrieved nationwide identification. “That’s why some nationalists prefer to say that it was America who made them so nationalistic,” he mentioned.

Because the International Instances grew, China’s strongest politicians watched with admiration. In 2004, when the paper revealed a column that criticised Chinese language journalists for unthinkingly accepting American media narratives in regards to the “struggle on terror”, the international minister, Li Zhaoxing, mentioned that he’d lengthy been ready to learn such an article. “Journalism is perhaps with out borders, however journalists do have motherlands,” wrote Li – within the International Instances – shortly after.

Later that yr, the president of the Individuals’s Day by day publishing group, Wang Chen, spoke at a seminar to debate the “International Instances phenomenon”. Wang mentioned that the minister of international affairs and the pinnacle of the abroad propaganda workplace had repeatedly advised him how a lot they cherished the paper, and that the International Instances exemplified methods to make propaganda readable. In shows to advertisers throughout this era, the publication would tout its shut ties with prime management, claiming that its readers included “almost 200 key leaders of the nation on the occasion central, the state council, the central army fee and the Nationwide Individuals’s Congress”. As quickly as every situation was revealed, the presentation claimed, particular messengers would ship the paper to Zhongnanhai, the walled compound the place a lot of the Communist occasion elite reside and work.

Since 2005, when he took over the paper as editor-in-chief, Hu has expanded the International Instances to an operation of 800 workers, publishing six days every week in Chinese language and in English. “We wanted to develop our affect, and we couldn’t try this with out utilizing English,” Hu advised me, explaining the choice to launch the English version in 2009.

Wanting again, the primary few years of the English-language International Instances can look like a wierd interlude within the paper’s historical past. Positioned in a rented workplace constructing exterior the Individuals’s Day by day compound, the English operation was largely separated from the Chinese language one. Somewhat than rigidly following the nationalistic line, it afforded journalists some area to report on extra delicate matters. Across the time of the English version’s launch, the International Instances employed a dozen international editors. Their job was to make sure that tales in English learn easily, however that they had little say on editorial choices. The English-language content material was written largely by Chinese language journalists. James Palmer, who labored on the International Instances for seven years and is now a deputy editor of the American journal International Coverage, advised me that within the early days, the newspaper’s English content material was about 60% “banal”, 20% “mad nationalistic stuff” and 20% “genuinely attention-grabbing”.

Hu differentiated his paper from the opposite English-language occasion outlet, China Day by day, by working tales on topics reminiscent of dissidents and LGBTQ rights. “The International Instances was attempting to make waves,” Jemimah Steinfeld, a British former editor, advised me. Staffers from this era remembered that Hu preferred to color himself as a drive for progress. All reforms start with rule-breaking, Hu advised a Chinese language journal in 2013. In case your kind of rule-breaking helps the nation, ultimately the federal government will give it approval. This, he mentioned, is how progress in China works.

In line with Wen Tao, a Chinese language reporter who labored for the English version, Hu advised workers to keep away from self-censorship and to pursue no matter they thought-about newsworthy. Wen’s items captured the on a regular basis struggles of life in Beijing a decade in the past: a poet criticising his native authorities’s plan to chop down 20,000 bushes with a purpose to prolong a street; a father attempting to advocate for meals security, after his kids obtained unwell from adulterated milk formulation, solely to be placed on trial himself. In February 2010, he broke a narrative in regards to the dissident artist Ai Weiwei and different native artists protesting in downtown Beijing towards the demolition of a residential complicated. Afterwards, Ai visited the newsroom of the English version, and was warmly welcomed.

The divergence between the English International Instances and the Chinese language International Instances was putting. “Their studies depicted two totally different Chinas,” wrote Wen on his private weblog in 2016. The place the Chinese language version demonised worldwide voices, the English version reported “some realities” in an try to point out the skin world that the Chinese language, too, loved a free press. “In case you didn’t have a look at the byline or the title of the paper, it may have very properly been a narrative from the Wall Road Journal,” Wen advised me.

It didn’t final. Not lengthy after his Ai Weiwei story, Wen was requested to submit his resignation. “The paper was trying to push boundaries, however I in all probability overdid it slightly bit,” Wen advised me. Round that point, he bumped into Hu within the elevator. Wen recalled the older journalist expressing frustration: typically you write your tales, hoping to make room for extra reporting like this – solely to search out your self being advised to take a giant step again. (Palmer advised me that the International Instances “had a tradition of two ‘critical errors’ each six months” and that Hu was “very usually” advised off by the propaganda authorities and different ministries.)

It’s laborious to inform to what extent, if any, Hu’s English-language International Instances mirrored his personal journalistic beliefs, or whether or not, as Wen urged, the licence given to its reporters was itself a sort of propaganda train, supposed to provide foreigners the impression that the Chinese language press loved larger freedom than it actually did and that he, too, was a actual reporter. On the very least, evidently throughout this era, on the English version, Hu was pretty dedicated to performing the position of a liberal-leaning editor. Palmer recalled that of their first assembly, Hu advised him, unprompted, that he wished democracy and freedom of speech in China, however that reform needed to be gradual. In Wen’s view, Hu is a deeply conflicted determine. “On the one hand, he wished to do journalism professionally, however alternatively, he couldn’t change his place as a celebration man,” he mentioned.

By 2011, as the federal government line on freedom of speech hardened, so did the editorial line of the International Instances. That yr, the authorities detained Ai Weiwei for 81 days, and the International Instances denounced him in a collection of Chinese language and English op-eds, together with one headlined “Ai Weiweis might be washed away by historical past”. “It was a really sudden pivot,” Palmer remembered. “And after that it simply turned worse and worse.” The American creator who now not contributes to the International Instances advised me: “Their enterprise mannequin appears to have switched to being utterly provocative and simply to piss individuals off.”

Typically, one former editor advised me, when an article appeared significantly inflammatory or outrageous, “we despatched up a pink flag, and they’d be like, ‘No, that’s precisely what we need to say.’”

Tlisted below are some ways to be an editor in chief, Hu advised me as his cellphones rang within the background. “Some individuals may use their power on managing, however I dedicate extra of my power to content material.” On the cellphone, Hu was well mannered and heat, in distinction to his aggressive on-line persona. He took lengthy pauses earlier than answering most questions, as if to compose mini-essays in his thoughts. Day by day, he advised me, his crew “displays” the web seeking standard topics, and as soon as they land on an concept, they put together a abstract of the difficulty and transient Hu on it. Then Hu will get to work, turning it right into a column. For each bit, his workers sometimes interview two or three consultants, largely authorities thinktankers and professors from prime universities. In line with Hu, which means his columns “don’t solely mirror my very own opinion, however take in the opinions of many individuals in our society. We symbolize a considerably mainstream soak up China.”

Because the area permitted to various views has shrunk, it has develop into more and more tough to evaluate what quantity of China’s 1.4 billion individuals share the International Instances’ worldview. Students, journalists, writers, legal professionals and activists have discovered their social media accounts suspended or erased due to their unspecified violation of the platform’s guidelines. These instances are so widespread and seemingly minor that they appeal to little worldwide consideration, however their collective impact is suffocating. In mainland China in the present day, censorship and self-censorship are just like the climate – you may complain about it, however you need to adapt to it. To insurgent is to undergo the potential for having your life ruined. Early final yr, a 36-year-old lady, Zhang Zhan, determined to report from Wuhan as a citizen journalist. She was quickly arrested and sentenced to 4 years in jail, and now, a number of months right into a starvation strike, she is on her deathbed. Most individuals in China don’t find out about Zhang Zhan, and people who do have a tendency not to consider what she represents – to take action would solely result in bother.

That doesn’t imply that party-approved figures reminiscent of Hu are past criticism in mainland China. Hu’s critics embrace former contributors to the International Instances, who really feel that since 2010, he has grown into an more and more absurd, even harmful, caricature of himself. “You might need observed that I hardly ever write for them any extra,” Shen Dingli, a professor of worldwide relations at Fudan College, who’s on the International Instances’s go-to checklist of consultants, advised me in an e mail. “The reason being their inclination in direction of excessive nationalism.” Xiang Lanxin, who is predicated exterior China, advised me one thing related, having been delay by Hu’s more and more crude politics. He was a frequent contributor to the International Instances, however he stopped within the early 2010s when he sensed that Hu was “now not curious about significant debates”.

Hu’s critics are significantly alarmed by enthusiasm for army options to issues. After a current border scuffle within the Himalayas with India, Hu argued that the Chinese language military ought to “prepared themselves to launch into battle at any second”. In one other column, Hu urged that China ought to construct up an arsenal of 1,000 nuclear warheads. In September, the International Instances revealed an op-ed headlined “Individuals’s Liberation Military jets will ultimately patrol over Taiwan”. Once I requested Hu about critics who accuse him of warmongering, he turned agitated and denied suggesting that China ought to begin a struggle. “What I mentioned is that if Taiwan began to assault us, then we should battle again with overwhelming drive,” he advised me. (One wonders what sort of motion would represent an “assault” in his view.)

To Xiang, Hu’s affect is much extra necessary than that of the headline-grabbing Wolf Warrior diplomats. The place diplomats will be silenced with one phrase from the highest, the emotions of Chinese language superiority that the International Instances stokes each day are far more durable to manage. “This newspaper has been main standard temper in a nationalist course for a very long time, and the implications of this are to not be taken calmly,” Xiang advised an interviewer final yr.

Sometimes, it may appear as if Hu is turning into a stranger in a sphere he helped construct. In Might, the Weibo account of the Central Political and Authorized Affairs Fee posted a picture titled China Ignition vs India Ignition, contrasting a current Chinese language rocket launch with Indian cremation – a reference to the nation’s surging Covid dying toll. When Hu criticised the publish and expressed sympathy for India’s plight, he was attacked by nationalists for being too smooth on certainly one of China’s principal rivals. A decade in the past, on social media, Hu had appeared to be the No 1 flag bearer for Chinese language nationalism. Now his standing isn’t so sure. On Weibo, whereas Hu was being criticised for inadequate nationwide satisfaction, one International Instances journalist requested: “Has Hu Xijin modified? Or, have the occasions modified?” The reply appeared clear.

Hu is 61, and rumours about his imminent retirement floor periodically. But he stays as zealous and filled with battle as he was three many years in the past. “He actually is the soul of the paper,” Wen advised me. “It’s very laborious to think about a de-Huxijinised International Instances.” The viewers he as soon as dreamed of as a younger reporter in Bosnia – readers who don’t unquestioningly admire western journalism and as a substitute cheer on their Chinese language counterparts – has materialised. Every of his Weibo posts are adopted by hundreds of feedback and tens of hundreds of likes.

Hu likes to name himself a shubianzhe, an antiquated time period for a guard stationed on the nation’s frontiers, holding it protected. In simply the previous week, fulfilling this responsibility has concerned insulting Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen, evaluating Hong Kong activist Nathan Legislation to a 6 January Capitol rioter, taunting the Australian prime minister, bickering with a Florida senator and posting quite a few cartoons highlighting American hypocrisy. It’s a ceaseless activity. For now, Hu fights on.

[ad_2]

Source link