[ad_1]

In March final 12 months, it was predicted that the worldwide journey shutdown would trigger worldwide arrivals to plummet by 20 to 30% by the tip of 2020.

Six weeks later, the UN World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) revised their warning: worldwide arrivals may fall by as much as 80% – equating to a billion fewer vacationers and the worst disaster within the historical past of the business.

“We’re again to ranges of journey we noticed 30 years in the past,” says Sandra Carvão, chief of tourism market intelligence on the company.

Eighteen months into the pandemic, home tourism is bouncing again, however efforts to open up worldwide journey have been hampered by the emergence of recent virus variants and by the variations in vaccine coverage and availability between international locations. Restoration is “very fragile and uneven”, based on the UNWTO. Virtually 50% of consultants it surveyed predicted that journey is unlikely to return to pre-pandemic ranges till no less than 2024.

The financial price of the worldwide tourism freeze is immense. A UNWTO report revealed with UN Convention on Commerce and Improvement on the finish of June forecast a lack of greater than $4tn (£2.9tn) to international GDP by the tip of 2021. Creating international locations are predicted to take the most important hit, with Central America struggling essentially the most.

The human price is huge. The challenges for hoteliers and tour operators are enormous, but additionally the pandemic has upturned thousands and thousands of lives in tourism communities throughout the globe. We go to 4 such communities – three in international locations on England’s red-list, one in an amber-listed location – to learn the way the disaster has affected folks and whether or not or not they need the vacationers to return.

Chitwan nationwide park, Nepal

Ashish Kadariya was born on the sting of a lush forest within the south of Nepal, house to the endangered Bengal tiger and one-horned rhino. Right this moment he finds himself in a unique type of jungle; certainly one of towering buildings, six-lane highways and oppressive warmth.

Kadariya, 25, was a information at Chitwan nationwide park, certainly one of south Asia’s high wildlife sanctuaries, however when the pandemic struck and vacationers stopped coming, he misplaced his solely supply of revenue. With few choices, he borrowed about £3,600 – way over his annual wage as a information – to pay a recruitment agent to search out him a job abroad. Now he works removed from the forest, patrolling the grounds of a luxurious lodge within the United Arab Emirates.

“We’ve got to work 12 hours a day, 30 days a month. I miss my nation and my career, however I don’t have any choices; due to Covid, I used to be jobless,” says Kadariya.

The pandemic has taken a devastating toll on Nepal. Tourism is a mainstay of the impoverished nation’s economic system, producing about 1.3m jobs and £550m a 12 months. Within the 12 months earlier than the pandemic, Nepal welcomed nearly 1.2 million guests – together with greater than 60,000 from the UK – however from April to December 2020, simply 9,417 arrived.

Vacationer numbers peak in spring and autumn, when the climate is at its most convivial, however the first wave worn out each seasons. This 12 months, as Nepal was gearing up for the spring peak, the second Covid wave struck. Now, as autumn approaches, the business faces a fourth season with out guests.

Nepal’s popularity as a world-class trekking and climbing vacation spot is well-known, however the wildlife reserves alongside its southern plains are equally spectacular. Chitwan nationwide park attracted greater than 142,000 international vacationers within the 12 months earlier than the pandemic, in addition to many hundreds of Nepalese, drawn by the prospect of sightings of tigers, rhinos and elephants.

The park sustains the livelihoods of hundreds; lodge employees, transport operators and guides. Rajendra Dhami, the top of the Nature Information Affiliation, says there are about 500 skilled guides in Chitwan. When requested what number of international guests he has seen since April, he hesitates after which solutions, “Three or 4”.

Dhami says guides are turning to farming or handbook labour to outlive, with some like Kadariya, going abroad. “The pandemic has given us a giant downside,” says Dhami. “We’re shedding our jobs and the federal government is doing nothing for us. We’re not fearful in regards to the coronavirus, we’re simply attempting to outlive.”

In addition to livelihoods, the pandemic has put conservation within the park in danger. As guides search for different work, important information about animal behaviour and biodiversity is being misplaced.

“The character information’s talent is unexplainable, you may’t discover it in a guide. So when tourism restarts folks might not get actual guides, actual nature lovers,” says Dhami.

Some are calling on the federal government to prioritise vaccines for guides and others within the business. “If the federal government can present vaccinations, then we will open Nepal in the identical manner as Dubai and the Maldives,” says Dhananjay Regmi, Nepal Tourism Board’s chief govt.

However vaccine rollout stays sluggish, with about 10% of the inhabitants totally vaccinated. Efforts to acquire vaccines have been hit by India’s resolution to halt vaccine exports. However, many blame Nepal’s political leaders who, they are saying, have been preoccupied with the infighting that has seen a current change of presidency, quite than tackling the virus.

“Vaccines are crucial for tourism, not just for the guides however for the vacationers. In the event that they don’t really feel comfy, they won’t come, but when we’re vaccinated, they may really feel protected,” says Dhami.

Till then, Nepalis like Kadariya are caught abroad in jobs they don’t need. “I completely remorse coming right here. My life was much better in Nepal. We guides are the primary pillars of tourism, however no one helps us. They don’t know our worth.”

by Pete Pattisson

Santiago de Okola, Bolivia

With the late morning solar shining by means of glassless home windows, Juan Callo, 58, is on his knees hammering on the basis beneath him in preparation for putting in new flooring. This isn’t the same old work for this Aymara farmer.

In Santiago de Okola, a 180-family village on the shore of the sacred Lake Titicaca, 150km from La Paz, a 15-year-old group tourism challenge has stalled because of the pandemic. Many townspeople have been left with out an revenue, surviving on what potatoes, quinoa and beans they will develop, as their households have carried out for generations.

“There are not any vacationers now, and there’s no supply of labor,” Callo says. “Not a single individual comes right here any extra.”

However Callo continues developing an area the place small teams of tourists can spend just a few nights in his house. Persons are investing their meagre financial savings to make enhancements for the day when vacationers return.

4 of Callo’s 5 kids now work in textile mills in Brazil, leaving him and his spouse to look after a teenage granddaughter. This case repeats itself throughout Bolivia’s altiplano, with many cities left within the arms of their oldest residents.

To guard its aged folks from Covid-19 Santiago de Okola shut itself off. Roads into city have been closed for 4 months from Might final 12 months, and once more in January and June this 12 months, coinciding with waves of instances within the space.

-

Juan Callo inspects his final crop of tarwi, a nutritious Andean bean. By August, most crops have been harvested, leaving folks to rely upon provides saved of their houses

These closures have been tough for Callo, a member of Santiago de Okola’s tourism affiliation (ASITURSO) – a gaggle of native households who organise customer actions together with homestays, day treks, conventional medication and weaving workshops. ASITURSO welcomed greater than 700 international vacationers and almost 450 Bolivians in 2019, with every spending, on common, $20 to $30 (£15 to £20) a day within the city.

Neighborhood tourism in Santiago de Okola started in 2006 as a imaginative and prescient of Tomas Laruta, a farmer who died from Covid-19 in January on the age of 94. He had labored as a information properly into his 80s, and had a dream of sharing this nook of Lake Titicaca with the world, to the advantage of his neighbours.

Right this moment, Laruta’s daughter Gabriela, a kindergarten trainer from the town of El Alto, has returned to the city to take up her father’s work.

-

Gabriela Laruta, daughter of ASITURSO founder Tomas Laruta, together with her niece at her father’s home, which the household is changing into bedrooms for vacationers

“My father’s dream was that everybody involves know his home and the group the place he lived, the place he was born,” says Gabriela. “That’s the reason he based this organisation, as a manner for everybody to unite, to allow them to work collectively to assist the group.”

However for the reason that pandemic Laruta’s dream has been on maintain. The city museum, a small room housing vintage handicrafts donated by neighbours, stays padlocked, its guestbook containing a single, dateless entry. A community-funded hostel and customer centre challenge that started three years in the past sits half-built.

Based on the nation’s chamber of tourism operators (CANOTUR), Lake Titicaca is certainly one of Bolivia’s high tourism locations, which embrace the Salar de Uyuni and the jungle areas of Rurrenabaque. An estimated 1.5 million international guests got here to Bolivia in 2019. Final 12 months, that crashed to only over 375,000, forcing companies throughout the nation to shut.

The Bolivian authorities tried to assist the sector, providing further vacation days to state employees. However Bolivia requires travellers to quarantine for 10 days on getting into the nation, although with out mechanisms to implement the measure. Officers are contemplating tips on how to raise this requirement with out risking public well being.

“We’ve got to dwell with the virus, we can’t keep locked up,” says Eliana Ampuero, Bolivia’s vice-minister of tourism. “To be human is to maneuver round, to alternate with different cultures, to know different locations. This pandemic doesn’t have to alter the very nature of being human.”

Bolivia is now properly into its peak tourism season of June to September. Callo has resigned himself to shedding a second 12 months of vacationers, however stays optimistic as he makes the enhancements for future guests.

“I hope travellers come again in order that we will begin working,” he says. “We wish to be with the vacationers once more, with our company.”

by William Wroblewski

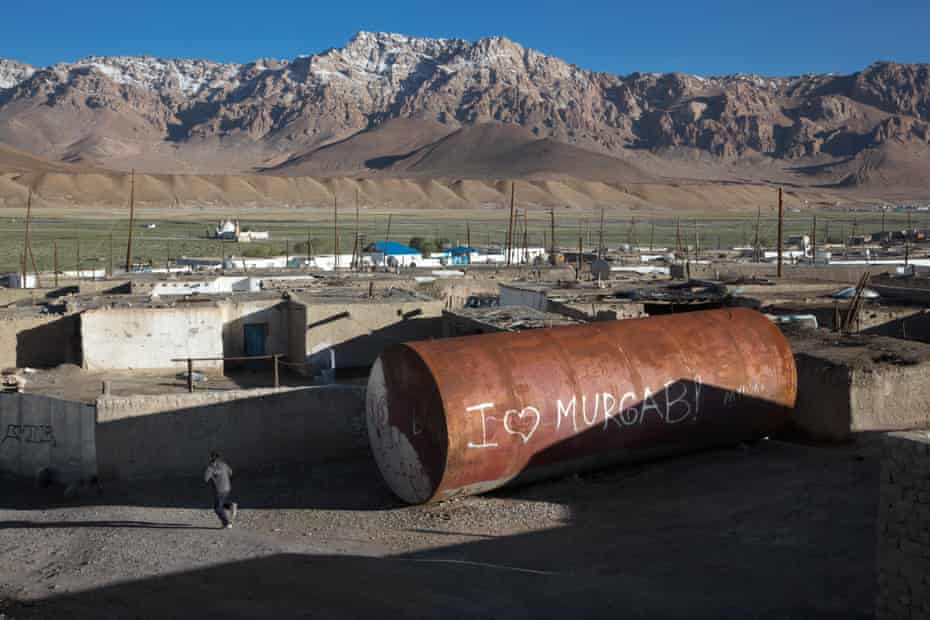

Pamir mountains, Tajikistan

“We don’t run a lodge. It is a guesthouse,” says Aigul Abdukadyrova, seated on the ground of his house in Murghab, a city excessive up in Tajikistan’s Pamir mountains. “Which means we sit and speak with our company, share our experiences and study theirs.”

Even in good instances, this city of about 7,500, in part of Tajikistan abutting Afghanistan and western China, appears like a lonely nook of the world.

At an altitude of just about 3,700 metres (12,000 ft) nothing however stubby grass thrives and the air is skinny. A ragged street portentously dubbed the Pamir freeway runs by means of a lunar panorama blanketed in snow for greater than half the 12 months. It’s only actually comfy for outsiders from Might to September.

Murghab’s heyday was when it was a Soviet navy outpost. When the bottom went in 2002, guests and jobs dried up. The mini-tourism growth of the final decade was a lifesaver for households just like the Abdukadyrovs, till Covid arrived.

The mushrooming of modest guesthouses meant these passing by means of have been leaving a few of their cash behind. On the final depend, there have been about 200 guesthouses within the autonomous Gorno-Badakhshan province (GBAO), Tajikistan’s easternmost area.

To get their enterprise began, the Abdukadyrovs took out a mortgage and constructed a brand new room at their easy, one-storey homestead. Aigul retired from her job in an area authorities workplace. Her husband and kids helped. For eight years they did properly.

“Our lifestyle modified quickly. The market was wholesome. Guests purchased handicrafts. Anyone who owned a automobile took the vacationers to see the sights,” she says.

Covid plunged Murghab and close by villages again into isolation. As if the pandemic weren’t unhealthy sufficient, an unpleasant row earlier this 12 months between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan has led to the closure of their shared Pamir border crossing. Excursions sometimes concerned driving vacationers, normally Europeans, from one nation to the opposite. Two successive seasons have been misplaced and it’s unclear when issues would possibly return to regular.

The ache has been felt throughout Tajikistan. In 2019, a move of 1.2 million guests generated about $250m (£180m) – a big quantity for the weak economic system. Final 12 months, leisure sector officers say numbers fell to 350,000 – and lots of of these have been unlikely to have been vacationers.

Lack of cash is crushing. However the solitude additionally hurts.

Aigul remembers with fondness the German scholar who got here one 12 months to review Kyrgyz, the language spoken by Murghab’s dominant ethnic group. They grew to become such good mates that he returned together with his mother and father the 12 months after.

“It appeared to me that we had turn into one household,” says Aigul. “I miss vacationers. Once they got here to us, we didn’t really feel lower off. Quite the opposite, I felt like we have been a part of this world.”

by Mehrangez Tursunsoza, translated by Peter Leonard

Cape Maclear, Lake Malawi

On the sandy roadside just a few metres from the shore of Lake Malawi, 48-year-old Potiphar Tilinga sits on a small wood chair chatting with the grocery shopkeeper throughout the street. Behind him, an array of crafts, together with salad spoons, fridge magnets, image frames and key fobs, is laid out underneath a thatched shade. Earlier than the pandemic, Tilinga made about 150, 000 Malawian kwacha (£130) a month promoting his wares. Now nobody comes to purchase his souvenirs.

“That is my life. I despatched my kids to non-public faculties however now I don’t know what to do. Nothing is working. I’ve 5 kids and take care of two orphans. All of them rely upon me. After the second wave of Covid-19, Malawians got here and gave us enterprise, however now it’s stopped utterly,” says Tilinga.

Tilinga lives in Chembe, identified to most outsiders as Cape Maclear, a village turned vacationer hotspot in Lake Malawi nationwide park. July and August are peak season, when vacationers fill its inexpensive lodges and hostels and spend their days kayaking across the freshwater lake’s rocky islands, swimming amongst tropical fish, and becoming a member of guided cultural excursions.

However as Malawi suffers a 3rd wave of coronavirus, the tourism business is enduring a second summer season with out guests. Earlier than Covid-19 about 800,000 vacationers visited every year; the pandemic has brought about a 75% drop in guests, leading to 35,000 job losses.

Amongst those that have misplaced jobs is Harry Dickson, 40, chair of the Cape Maclear tour information affiliation, whose 62 members run actions akin to climbing, village excursions and conventional dances.

“[My work meant] I may afford to purchase fundamental requirements and pay college charges for my brothers and sisters and assist my mother and father. I’ve been taking good care of my seven kids from that cash; now there may be nothing. Worldwide tourism is totally gone. Malawians are scared to return right here. We’re residing by probability, not selection,” says Dickson.

“Cape Maclear could be very robust in the intervening time, particularly fishing and tourism, the predominant sources of livelihoods,” says Allan Joffe, 49, a Briton who came visiting Chembe 14 years in the past and stayed. He owns Mgoza lodge with chalets and dorms. His spouse is a health care provider at an area clinic. Earlier than Covid, Joffe employed 32 folks; now, with the lodge working at 20% capability, he has simply 19 employees, most on diminished wages and hours. Some folks have been pressured to go away the city as a result of they will now not afford to dwell there.

In addition to these straight employed, there are hundreds extra who rely upon the vacationer greenback. “Folks used to return day by day and promote tomatoes, onions, and different merchandise, even from Blantyre [235km south] however we will’t purchase from them now. The knock-on impact of getting no vacationers in Cape Maclear is large,” Joffe says.

by Charles Pensulo

[ad_2]

Source link